Digital Legal TALKS program

The Digital Legal Talks conference was held fully online on 2 December 2020, from 1-5 pm (CET). It was a meeting place for academics, practitioners, students, policymakers and others who share an interest in the dynamic and exciting field of Digital Legal Studies.

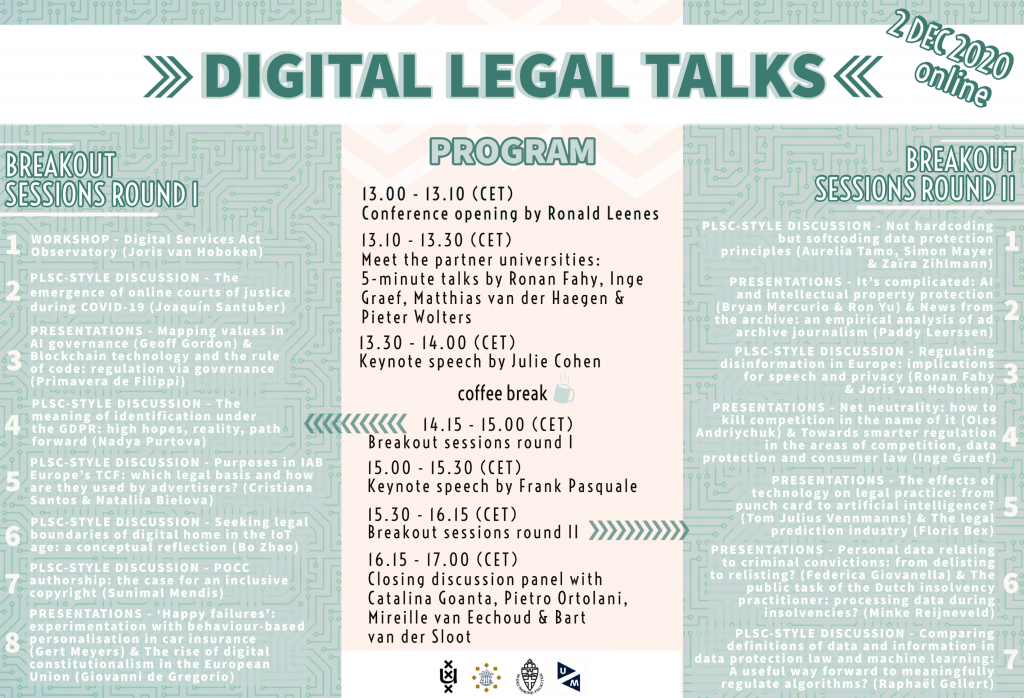

The program IN A NUTSHELL:

Kick-off | 13.00 – 13.10 (CET)

Conference opening & introduction to the Digital Legal Studies collaboration by prof. dr. Ronald Leenes.

Meet the partner universities | 13.10 – 13.30 (CET)

Get to know the research and the researchers from our collaboration’s four partner universities – the University of Amsterdam, Tilburg University, Radboud University Nijmegen and Maastricht University – and learn what each team brings to the table in terms of its unique approach and research focus. Speakers: dr. Ronan Fahy (UvA), dr. Inge Graef (TiU), dr. Pieter Wolters (RUN) and dr. Matthias van der Haegen (UM).

Keynote speech | 13.30 – 14.00 (CET)

Keynote speech by Julie Cohen, professor of Law & Technology at Georgetown Law School.

Coffee break | 14.00 – 14.15 (CET)

Breakout sessions – Round 1 | 14.15 – 15.00 (CET)

First round of interactive breakout sessions covering a multitude of topics and perspectives. Participants could choose from 8 workshops, paper presentations and interactive PLSC-style discussions with researchers working across disciplines both inside and outside the Digital Legal Studies collaboration.

Keynote speech | 15.00 – 15.30 (CET)

Keynote speech by Frank Pasquale, professor of Law at Brooklyn Law School.

Breakout sessions – Round 2 | 15.30 – 16.15 (CET)

Round two! This time, there were 7 breakout sessions to choose from. See the abstracts of all papers that were discussed and presented a little further down.

Closing panel | 16.15 – 17.00 (CET)

Four panelists – one from each partner university of the Digital Legal Studies collaboration – drew on their unique expertise to discuss challenging and controversial questions faced by the field of Digital Legal Studies. Speakers: dr. Pietro Ortolani, dr. Catalina Goanta, prof. dr. Mireille van Eechoud and dr. Bart van der Sloot.

breakout sessions & abstracts

Participants split up into smaller groups for two rounds of breakout sessions that explored different topics within the field of Digital Legal Studies. The sessions varied from workshops to presentations or PLSC-style paper discussions.

Breakout sessions – Round I

Round 1 / session 1

WORKSHOP | Digital Services Act Observatory

Joris van Hoboken

Abstract. The Digital Services Act (DSA) will set the terms for the relation of European democracies with dominant digital platforms for the coming decades. The DSA legislative package is very complex and engages a wide variety of economic, social, and political issues, impacting the conditions for the effective exercise of fundamental rights and the protection of democratic values and economic welfare. Considering the breadth of perspectives feeding into the legislative process, the DSA covers a number of different approaches to the regulation of platforms, with significant potential trade-offs between them. As such, we are launching the DSA Observatory at the Institute for Information Law, University of Amsterdam, and our goal with the DSA Observatory is to identify opportunities for the academic community at UvA and elsewhere to engage in the DSA process and provide independent, robust input for policy makers and other relevant stakeholders. The DSA Observatory will provide analysis of policy documents, coordinate engagement on DSA proposals by other researchers at UvA as well as our broader network of platform regulation experts in academia. On the basis of our expertise and analysis, it will interact with and provide value to the DSA related activities of other relevant stakeholders, including civil society organisations, regulators, and industry.

Round 1 / session 2

PLSC-STYLE PAPER DISCUSSION | ‘The Emergence of Online Courts of Justice During COVID-19’

Joaquín Santuber, Christian Dremel and María José Hermosilla

Abstract. Access to justice is a pressing issue around the world. An estimated 70 percent of the world population cannot solve their legal problems through justice systems. During early 2020, courts had to leave their physical world and go online overnight due to COVID 19. The way courts function and organize their work has a tremendous impact on making justice accessible. Little research has been done to understand how courts, judges, prosecutors, and defendants’ practices are re-configured with the adoption of new technology. This research looks at the – unplanned- adoption of communication technology in a criminal and a civil court in Chile and how the new practices are configured. We take a sociomaterial approach to study the emergent phenomena of the sociotechnical complexities of how judges, lawyers, and clerks react to unforeseen technological appropriation in their work environment. Using qualitative interviews, video analysis of online hearings, and reviewing legal documents, we draw conclusions to better design resilient sociotechnical-judicial systems to make law and justice more accessible.

Round 1 / session 3

TWO PAPER PRESENTATIONS | ‘Mapping Values in AI Governance’ & ‘Blockchain Technology and the Rule of Code: Regulation via Governance’

Geoff Gordon (presentation I) & Primavera de Filippi (presentation II)

Abstract I (‘Mapping Values in AI Governance’). Our paper proposes a new methodological framework by which to analyze legal-regulatory problematics of algorithmic decision-making systems. We propose a rigorously materialist inquiry, in which legal-regulatory practices and technical code are understood as mutually implicated and enfolded in socio-technical assemblages. Our interest is a fundamental one, to discern what is valorized in this new regulatory ecology. Accordingly, we target terms and tokens of value as they are produced, reproduced, incorporated and translated among design processes in constitutive material context. Intervening in the overarching debate into whether and how AI may share or conform to democratic values, our study aims at conceptually prior questions of how values are generated and distributed in concrete settings with regulatory consequences. In other words, rather than asking which values AI should satisfy in contested governance contexts, we address how values manifest and ‘map’ among computational and socio-technical interactions in the first place. On this basis, our framework aims at a grounded understanding of the actual regulatory effects of socio-technical interactions involving AI components.

Abstract II (‘Blockchain Technology and the Rule of Code’). The regulatory challenges of blockchain technology are essentially due to the decentralized nature of blockchain-based networks, which makes it difficult for governments or other centralized authorities to control or influence their operations. This paper analyses the interplay between the “rule of law” and the “rule of code” for the regulation of blockchain systems. It then investigates the tools available to governments to address the regulatory challenges raised by this novel technology, and the extent to which the regulation of blockchain systems can be better achieved through innovative governance practices.

Round 1 / session 4

PLSC-STYLE PAPER DISCUSSION | ‘The Meaning of Identification under the GDPR: High Hopes, Reality, Path Forward’

Nadya Purtova

Abstract. Identification both as a process of identifying someone and the fact of being identified is one of the boundary concepts of data protection law. It separates the data that is personal, i.e. relating to an identified or identifiable natural person, from non-personal, and triggers the applicability of the GDPR. Yet, little attention is paid to what identification is. The mainstream literature is focused on the meaning of identifiability as a legally relevant chance of identification. Yet, the meaning of identifiability is derived from and secondary to the meaning of identification. Any discussion about the possibility of identification not grounded in a thorough understanding of identification is inadequate. The chief issue tackled in this paper is the meaning of identification under the GDPR.

The Article 29 Working Party in its non-binding opinion defines identification as distinguishing a person from the group, but the EUCJ seems to have invalidated this approach in Breyer: while the very point of IP addresses is to distinguish one web visitor from the rest, the Court ruled that this information did not relate to an identified person. This ruling has a potential to restrict the protective reach of the GDPR and exclude some instances of individual profiling, facial recognition and other invasive practices from its scope. This paper aims to reverse this effect.

The paper begins with a socio-technical conceptualization of identification. To operationalize this concept, and relying on the four types of identification according to Leenes and seven types of identity knowledge according to Marx, the paper offers an integrated typology of identification consisting of five identification types. Personalization is distinguished as a new type of identification. While following the Working Party’s approach, all five types would constitute direct or indirect identification for the purposes of the GDPR, only one – look-up identification – would be included if the restrictive Breyer approach is followed. Yet Breyer should and can be read differently. First, the principle of effective and complete protection of the data subjects precludes construing the scope of the GDPR narrowly. Second, Breyer has to be read accounting for the specific context of the case: the dispute concerned retention of the IP addresses and access logs after the website consultation, rather than processing of the dynamic IP addresses per se. This does not preclude that a website visitor would be regarded as identified by a dynamic IP address under different circumstances, e.g. during the browsing session. Under these particular circumstances, a dynamic IP address cannot directly identify a natural person. This contextual reading of Breyer brings all five types of identification into the scope of the GDPR.

The paper considers the implications of this argument for the European data protection law, focusing in particular on the question of the regulatory overreach and if the GDPR is equipped (and should be equipped) to handle equally the full spectrum of the identification practices and the related problems. The result of such interpretation is that the scope of data protection law grows broad. But it also reveals that what we want to address by this broad interpretation is indeed a variety of different practices and problems, which may warrant different approaches to legal protection.

Round 1 / session 5

PLSC-STYLE DISCUSSION | ‘Purposes in IAB Europe’s TCF: which legal basis and how are they used by advertisers?’

Cristiana Santos and Nataliia Bielova

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), Data Protection Authorities (DPAs) and the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) discuss purposes for data processing and the legal bases upon which data controllers can rely on: either “consent” or “legitimate interests”. We study the purposes defined in IAB Europe’s Transparency and Consent Framework (TCF) and their usage by advertisers. We analyze the purposes with regard to the legal requirements for defining them lawfully, and suggest that several of them might not be specific or explicit enough to be compliant. Arguably, a large portion thereof requires consent, even though the TCF allows advertisers to declare them under the legitimate interests basis. Finally, we measure the declaration of purposes by all advertisers registered in the TCF versions 1.1. and 2.0 and show that hundreds of them do not operate under a legal basis that could be considered compliant under the GDPR.

Round 1 / session 6

PLSC-STYLE PAPER DISCUSSION | ‘SEEKING LEGAL BOUNDARIES OF DIGITAL HOME IN THE IOT AGE: A CONCEPTUAL REFLECTION’

Bo Zhao

Abstract. No doubt, home is a sanctuary place, the center of privacy. One of many challenges to contemporary home protection law is the much blurred, or collapsed, home boundaries due to the fact that the traditional home has become a hybrid of physical space and virtual space, and the shift of a considerable number of home activities and home assets into virtual spaces outside the traditional home (physical) boundaries, i.e., walls, fences, roofs, and windows. Thus, to find feasible home boundaries becomes rather critical in future law development, because this will help clarify the legal uncertainties under the current legal framework and upgrade traditional home protection to the new home environments.

Thus this conceptual paper seeks to: a) conceptualize digital home by reviewing the recent tech-legal developments (mainly the US and EU), b) find feasible virtual boundaries of the digital home that may extend the traditional home protection to the extended virtual space, and c) further reflect on the difficulty the contemporary law confronts in coping with the growing conflict between virtuality and physicality, through the lens of the home protection case.

The article tentatively argues that a pure “digital home” that is geo-location free and device independent can be possible and may exist in the online environment in view of the quick deployment of cloud computing and IoT technologies. This digital home as a virtual container/bubble is characterized by mobile, mosaic and individual nature, spreading over the internet, and thus differs much from the modern home configurations; and new home (virtual) boundaries that can play a role of legal proxy are some key security measures used by home occupants (at the moment) to excise sufficient control over the virtual home space (cross-platforms, cross-services), such as identification and authentication measures associated with the home occupant’s service accounts, as well as encryption and firewalls under certain conditions.

Round 1 / session 7

PLSC-STYLE PAPER DISCUSSION | ‘POCC authorship: The case for an inclusive copyright’

Sunimal Mendis

Abstract. Public open collaborative creation (POCC) constitutes an innovative form of collaborative authorship that is emerging within the digital humanities. At present, the use of the POCC model can be observed in many online creation projects the best known examples being Wikipedia and free-open source software (FOSS). This paper presents the POCC model as a new archetype of authorship that is founded on a creation ideology that is collective and inclusive. It posits that the POCC authorship model challenges the existing individualistic conception of authorship in exclusivity-based copyright law. Based on a comparative survey of the copyright law frameworks on collaborative authorship in France, the UK and the US, the paper demonstrates the inability of the existing framework of exclusivity-based copyright law (including copyleft licenses which are based on exclusive copyright) to give adequate legal expression to the relationships between co-authors engaged in collaborative creation within the POCC model. It proposes the introduction of an ‘inclusive’ copyright to the copyright law toolbox which would be more suited for giving legal expression to the qualities of inclusivity and dynamism that are inherent in these relationships. The paper presents an outline of the salient features of the proposed inclusive copyright, its application and effects. It concludes by outlining the potential of the ‘inclusive’ copyright to extend to other fields of application such as traditional cultural expression (TCE).

Round 1 / session 8

TWO PAPER PRESENTATIONS | ‘Happy failures: Experimentation with behaviour-based personalisation in car insurance’ & ‘The Rise of Digital Constitutionalism in the European Union’

Gert Meyers (presentation I) & Giovanni De Gregorio (presentation II)

Abstract I (‘Happy Failures’). Insurance markets have always relied on large amounts of data to assess risks and price their products. New data-driven technologies, including wearable health trackers, smartphone sensors, predictive modelling and Big Data analytics, are challenging these established practices. In tracking insurance clients’ behaviour, these innovations promise the reduction of insurance costs and more accurate pricing through the personalisation of premiums and products. However, insurers need to provide actuarial evidence on the relation between, e.g., driving style and the experience of loss before they are allowed by law to discriminate on the latter basis. Yet without collecting these data in real-time situations it is impossible to build an evidence base for the use of telematics data in car insurance. This means that insurers currently find themselves in a catch-22 where the usefulness of these data is unclear until they are proven to be useful. Building on insights from the sociology of markets and Science and Technology Studies (STS), this article investigates the role of economic experimentation in the making of data-driven personalisation markets in insurance. We document a case study of a car insurance experiment, launched by a Belgian direct insurance company in 2016 to set up an experiment of tracking driving style behavioural data of over 5000 participants over a one-year period. Based on interviews and document analysis, we outline how this in vivo experiment was set-up, which interventions and manipulations were imposed to make the experiment successful, and how the study was evaluated by the actors. Using JL Austin’s distinction between happy and unhappy statements, we argue how the experiment, despite its failure not to provide the desired evidence (on the link between driving style behaviour and accident losses), could be considered a ‘happy’ event. We conclude by highlighting the role of economic experiments ‘in the wild’ for the making of future markets of data-driven personalisation.

Abstract II (The Rise of Digital Constitutionalism in the European Union). In the last twenty years, the policy of the European Union in the field of digital technologies has shifted from a liberal economic perspective to a constitutional approach. The development of digital technologies has not only challenged the protection of individuals’ fundamental rights such as freedom of expression, privacy and data protection. Even more importantly, this technological framework driven by liberal ideas has also empowered transnational corporations operating in the digital environment to perform quasi-public functions in the transnational context. These two drivers have led the Union to enter into a new phase of modern constitutionalism (i.e. digital constitutionalism). This evolution is described by three constitutional phases: digital liberalism, judicial activism and digital constitutionalism. At the end of the last century, the Union adopted a liberal approach to digital technologies to promote the growth of the internal market. A strict regulation of the online environment would have affected the internal market, exactly when new technologies were going to revolutionize the entire society. The end of this first season resulted from the emergence of the Nice Charter as a bill of rights and new challenges raised by transnational private actors in the digital environment. In this phase, the ECJ has played a pivotal role in moving the Union standpoint from fundamental freedoms to fundamental rights. This second phase has only anticipated a new season of constitutionalism based on codifying the ECJ’s judicial efforts and limiting powers exercised by online platforms. The path of European digital constitutionalism is still at the beginning. A fourth phase of digital constitutionalism in Europe would raise as an answer to digital challenges in the global context.

Breakout sessions – Round II

Round 2 / session 1

PLSC-STYLE PAPER DISCUSSION | ‘Not Hardcoding but Softcoding Data Protection Principles’

Aurelia Tamo-Larrieux, Simon Mayer and Zaira Zihlmann

Abstract. The delegation of decisions to machines has revived the debate on whether and how technology should and can embed fundamental legal values within its design. This debate builds upon a rich literature on techno-regulation as well as the quest for legal protection by design. While these debates have predominantly been occurring within the philosophical and legal communities, the computer science community has been eager to provide tools to overcome some challenges that arise from ‘hardwiring’ law into code. What emerged is the formation of different approaches to legal code, i.e. code that adapts to legal parameters. Within this article, we discuss the translational, systemic, and moral issues raised by implementing legal principles in software. While our findings stem from an investigation of the General Data Protection Regulation and thus focus on data protection law, they apply to legal code across legal domains. These issues point towards the need to rethink our current approach to design-oriented regulation and to prefer ‘soft’ implementations of legal code over ‘hard’ approaches. Softcoding has the advantage to create flexible systems that remain transparent, contestable, and malleable and thereby allow for disobedience, which is necessary to ensure the possibility of moral responsibility and overall legitimacy of legal code.

Round 2 / session 2

TWO PAPER PRESENTATIONS | ‘It’s complicated: AI and Intellectual Property Protection’ & ‘News from the Archive: An Empirical Analysis of Ad Archive Journalism’

Ron Yu (presentation I) & Paddy Leerssen (presentation II)

Abstract I (‘It’s Complicated’). How the IP system deals with AI is far more complicated and involved than it might initially appear yet this issue is both contemporary and pressing. So important that the World Intellectual Property Office held multiple ‘Conversation on IP and AI’ events in September 2019, July 2020 and November 2020.

The urgency behind lies, inter alia, in the fragmentation of norms, rejected patent applications by US, UK and Europe patent offices and the progress of AI to the point where AI can spontaneously and autonomously create copyrightable content, registerable designs, inventions and even non-existent but realistic looking persons.

AI is integral to many systems we use today and is also changing the nature of the process of buying goods and services on e-commerce platforms in a way in which has important implications for commerce and market competition. The time is thus ripe to address the profound role the IP system has on AI, not only because it can protect but also serve to block access to key AI technologies. This paper evaluates substantive issues relating to AI, IP in the data used by an AI system and the question of the purpose of IP and the consequences of AI as an IP holder.

Abstract II (‘News from the Archive’). Facebook’s Ad Library is a widely-publicized and controversial initiative to create a public registry of microtargeted online advertisements. These practices have received growing regulatory attention from lawmakers across the globe, as a new model to create transparency and accountability in these otherwise opaque services. However, the critical literature on transparency regulation warns that the ideal of transparency often fails to fulfil its promise of accountability in practice. With these considerations in mind, this article offers a first attempt to take stock of the Ad Library’s actual impact in practice.In particular, this paper focuses on its reception by journalists as a key user group, and explores whether and how they have started to use the Ad Library as a resource in their reporting. Given the exploratory nature of this research, this article adopts a mixed-methods approach, combining content analysis with interviews to generate a typology of journalistic use cases. These findings are then discussed in light of regulatory theory in order to critically evaluate the Ad Library’s contribution to ideals of transparency and accountability in online advertising.

Round 2 / session 3

PLSC-STYLE PAPER DISCUSSION | ‘Regulating Disinformation in Europe: Implications for Speech and Privacy’

Joris van Hoboken and Ronan Fahy

Abstract. This paper examines the ongoing dynamics in the regulation of disinformation in Europe, focusing on the intersection between the right to freedom of expression and the right to privacy. Importantly, there has been a recent wave of regulatory measures and other forms of pressure on online platforms to tackle disinformation in Europe. These measures play out at the intersection of the right to freedom of expression and the right to privacy in different ways. Crucially, as governments, journalists and researchers seek greater transparency and access to information from online platforms to evaluate their impact on the health of their democracies, these measures raise acute issues related to user privacy. Indeed, platforms that once refused to cooperate with governments in identifying users allegedly responsible for disseminating illegal or harmful content are now expanding cooperation. However, platforms are invoking data protection law concerns in response to recent efforts at increased transparency. At the same time, data protection law provides for one of the main systemic regulatory safeguards in Europe. It protects user autonomy in relation to data-driven campaigns, requiring transparency for internet audiences about targeting and data subject rights in relation to audience platforms such as social media companies.

Round 2 / session 4

TWO Paper presentationS | ‘NET NEUTRALITY: HOW TO KILL COMPETITION IN THE NAME OF IT’ & ‘TOWARDS SMARTER REGULATION IN THE AREAS OF COMPETITION, DATA PROTECTION AND CONSUMER LAW: WHY GREATER POWER SHOULD COME WITH GREATER RESPONSIBILITY’

Oles Andriychuk (PResentation 1) & Inge graef (presentation 2)

Abstract I (‘Net Neutrality’). At first glance, Net Neutrality represents a noble, uncontroversial idea: all Internet traffic created by Content and Application Providers (CAPs) must be delivered to end users by Internet Service Providers (ISPs) without discrimination, on the first come first served principle. The conventional narrative traces the origins and the evolution of the principle back to the very emergence of the Internet, referring to its founding fathers’ numerous commentaries that the idea of Net Neutrality is the cornerstone of the very architecture of the Internet, its Alpha and Omega.

This paper seeks to demonstrate that the principle of Net Neutrality – at least in the form it is adopted in the EU/UK legislation – is (i) anticompetitive; (ii) does not serve the interests of EU/UK digital sovereignty as articulated in the first two parts of the paper; (iii) was introduced to the advantages of its real beneficiaries – Big Tech companies; (iv) cements status quo and slows down innovation and new entrants; (v) delegitimises an important competitive parameter – Internet speed; and (vi) should be modified by softening its requirements and allowing some controlled instances of commercial traffic management.

To substantiate these propositions, this part of the paper begins with highlighting the historical context, in which the idea of Net Neutrality was eloquently shaped and successfully promoted. It then looks at the main economic parameters of the principle and demonstrates who, where, how and why exploits wrong interpretation of those parameters. It then demythologises 7½ false assumptions about Net Neutrality, which allows at the end to shape the key elements of the regulatory proposal for the softening the current rules. The paper finishes with explaining the mechanics of functioning of the newly proposed rules.

Abstract II (‘Towards smarter regulation in the areas of competition, data protection and consumer law’). Based on a mix of conceptual insights and findings from cases, this paper discusses three ways in which the effectiveness of regulation in the areas of competition, data and consumer protection can be improved by tailoring substantive protections and enforcement mechanisms to the extent of market power held by firms. First, it is analysed how market power can be integrated into the substantive scope of protection of data protection and consumer law, drawing inspiration from competition law’s special responsibility for dominant firms. Second, it is illustrated how more asymmetric and smarter enforcement of existing data protection rules against firms possessing market power can strengthen the protection of data subjects and stimulate competition based on lessons from priority-setting and cooperation by consumer authorities. Third, it is explored how competition law’s special responsibility for dominant firms can be further strengthened in analogy with the principle of accountability in data protection law. Similarly, it is discussed how positive duties to ensure fair outcomes for consumers are developed in consumer law. The analysis offers lessons for improving the ability of the three regimes to protect consumers by imposing greater responsibility on firms with greater market power and thus posing greater risks for consumer harm.

Round 2 / session 5

TWO PAPER PRESENTATIONS | ‘The Effects of Technology on Legal Practice: From Punch Card to Artificial Intelligence?’ & ‘The Legal Prediction Industry’

Tom Julius Vennmanns (presentation I) & Floris Bex (presentation II)

Abstract I (‘The Effects of Technology on Legal Practice’). It is difficult to come up with any events after World War II which have led our entire global society to recognise that The Times They Are A‐Changin’ as clearly as the global crises of 2020 has done. The COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath in particular have revealed that almost everything we once considered stable and sustainable is actually built on quite shaky ground. But the crisis has also brought out the best in our coexistence, seeing that societies in many countries have shown that they are capable of finding creative solutions to overcome the current challenges. Digital technologies have played a crucial role in the world’s response to the COVID-19 crisis. Just think of modern methods of telecommunication such as video conferencing, which have made an immense contribution to maintaining the economy and work processes, or the various corona tracking apps, which are helping to stop the spread of the virus. It can be assumed that the harmful consequences of the pandemic would have grown even greater if those digital solutions had not been available. Just as almost every area of life is affected by the pandemic, so are the law itself and legal practice.

Immediate examples of the effects on legal practice can be found in the countless suspended litigations or arbitrations, or the fact that law firms were unable to conduct physical meetings with clients or other colleagues. Digital solutions such as videoconferencing, which are practice-preserving in other areas, also helped in legal practice to maintain ‘business (almost) as usual’ throughout the crisis. Unfortunately, the digitisation of justice and legal practice has not progressed beyond approaches and pilot projects in some fields and jurisdictions. For example, in some German federal states (Federal States of Bremen and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania) there is not a single court that provides an official facility for video conferencing. Also, digital file processing in litigation is beyond current technical capabilities in many jurisdictions around the world. In general, old-fashioned means such as faxing are still dominating the traditional court proceedings while they are hardly used anymore outside the courtroom. Therefore, it seems as if these very preliminary observations confirm the topicality of Luhmann’s provocative statement, expressed half a century ago: ‘Law and data processing have as much in common as cars and deer: Mostly nothing, but sometimes they collide.’

Legal tech solutions in particular could offer a promising approach to making legal practice fit for the digital age. According to the simplest definition, legal tech comprises digital solutions that support or perform partly or entirely legal work. Think for example of software and applications that support or could support the daily work of judges, arbitrators and legal practitioners. These include special programs for the creation of legal documents, special clouds allowing legal practitioners and their clients to share documents as well as tailor-made translation software for the legal environment. In addition, legal tech solutions exist for law enforcement, such as Online Dispute Resolution (ODR) portals. The use of ODR, smart contracts and blockchain technologies in particular are capable of improving access to justice. Take, for example, small claims or hundreds of thousands of consumers with scattered damages who have so far refrained from enforcing their rights in state courts because the costs, time and emotional hurdles were disproportionate to the damage suffered. These legal tech possibilities create a new dynamic structure within the legal sector: law firms suddenly face competition from legal tech start-ups, questioning the fundamental need for human legal professionals.

This chapter will show how digital technology has influenced legal practice in the past and how it is changing the profession of today and of the future. In a first step, the upcoming section will examine the question of which systematic challenges exist within the interplay of digital technologies and legal practice. How does legal practice actually differ from the function of technological processes and can both worlds be brought together in a meaningful and effective way? Section C of this contribution analyses the different stages of development in the relationship between digital technology and legal practice. Questions regarding the evolving requirement profiles and sought-after qualities of lawyers in the various professional groups will also be addressed. Part D deals with the problems that can arise from the bond of legal practice and the latest generation of digital technologies. How will the legal labour market change and will human service providers still be needed in the future, in a world possibly based on AI? What is the position of the legislator and how can he influence future developments? The outlook concludes this contribution by shedding some light on the future of legal education in the digital age.

Abstract II (‘The Legal Prediction Industry’). The legal prediction industry is on the rise: under the heading ‘Artificial Intelligence (AI) for the judiciary’ there are many discussions about the use of AI algorithms for predicting outcomes of legal cases. Despite the enthusiasm in the media about the opportunities offered by these algorithms, there are also sceptical voices from the (legal) academic world.

So are these predictive algorithms a meaningless hype or can they still be useful? We try to provide some tentative answers to this question. We first discuss several types of legal predictive algorithms, continuing with some important issues concerning determining the quality of predictive algorithms. We then discuss our main question, how the various types of predictive algorithms can be useful for legal academic research, for justice-seeking parties and for the judiciary. We will argue that there is definitely a hype surrounding predictive algorithms but that they cannot be disqualified as meaningless, since they can be useful in the law in various ways.

Round 2 / session 6

TWO PAPER PRESENTATIONS | ‘Personal data relating to criminal convictions: from delisting to relisting?’ & ‘The public task of the Dutch insolvency practitioner: processing data during insolvencies?’

Federica Giovanella (presentation I) & Minke Reijneveld (presentation II)

Abstract I (‘Personal data relating to criminal convictions’). The 2019 case GC et al. v. CNIL concerned some requests for delisting, including one for personal data relating to criminal convictions. While the CJUE specified that it is for the operator of a search engine to assess whether the data subject has a right to have this information delisted, it also added that ‘the operator is in any event required, at the latest on the occasion of the request for de-referencing, to adjust the list of results in such a way that the overall picture it gives the internet user reflects the current legal position’ of the data subject’.

Although this statement was not part of the ruling, the way in which it is written seems to introduce a new duty on search engine operators and a corresponding right of data subjects for data relating to criminal conviction. Has the Court introduced a ‘right to relisting’? And would such new approach be a better balance between personal data protection and freedom of expression?

Building on the existing literature on the right to delisting, the article considers whether a right/duty to relisting would make up for the shortcomings of the right to relisting as we currently know it.

Abstract II (‘The public task of the Dutch insolvency practitioner’). On the basis of Section 68 of the Dutch Bankruptcy Act (DBA), an insolvency practitioner [Dutch: curator] is charged with the management and liquidation of the insolvent estate. This means, among other things, that he has to take care of all the administration and data carriers of the bankrupt company, find ways to liquidate the business continue the business (such as a going-concern sale or piecemeal liquidation) and manage the estate.

In the performance of these activities, the insolvency practitioner processes personal data in virtually every bankruptcy: there are personal data in the administration of the company, in e-mails from the directors, in the personnel administration, in the customer administration and so on. The insolvency practitioner processes this personal data by searching and copying it at least, but he can also publish, share or sell certain personal data.

These personal data also play an increasingly important role in bankruptcies: in these more and more digital times, the goodwill of a company, including customer data such as account information, tracking data, and ordering information, becomes more valuable. The insolvency practitioner might sell complete customer files containing personal and payment details in order to generate revenues for the creditors of an insolvent company.

In a letter from January to the Association of Insolvency Lawyers (INSOLAD), the Dutch Data Protection Authority [Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens] has indicated that the insolvency practitioner will often have to base the processing of personal data in bankruptcies on the prior consent of the data subjects, certainly in the case of a liquidation or a restart. This is quite unattractive and impractical for the insolvency practitioner, given the strict rules regarding consent. After all, the bankruptcy benefits from speed and low costs. A going-concern sale of a company will only be successful when it happens quick and fast: waiting for all data subjects to consent will lead to an impossibility for the IP to sell the company. This might have huge economic consequences and the GDPR would hamper the insolvency proceeding.

That is why the Minister for Legal Protection has now submitted a proposal for legislation. In this proposal, he intends to enshrine that the insolvency practitioner may process personal data in the context of his task of general interest as if formed by article 68 DBA (managing and liquidating the insolvent estate). The proposed Article 68a DBA contains a non-exhaustive list of acts that fall within this public interest-task. The list includes acts such as: investigating the causes of the insolvency, including possible notifications to the competent authorities; writing, publishing and keeping available for a reasonable period of time the bankruptcy report; providing information to the creditors’ committee.

This would really help the insolvency practitioner, if the legislative proposal would make clear when the IP can process what personal data. However, it is not clear from this legislative proposal nor the accompanying explanatory memorandum what processing is necessary for the liquidator to carry out his task in the public interest. This is firstly because the task of the insolvency practitioner is not clear: it is largely up him or her to determine how to fulfill this task of managing and liquidating. The IP has a great deal of discretion to determine how to settle the insolvency. Even when it would be clear what actions fall under the task of the insolvency practitioner, it still does not follow from the explanatory memorandum or the law which processing is necessary.

Not a lot of ‘European’ attention has been given to the public interest-task so far. Can a trustee in bankruptcy have a task in the public interest? And does art. 68a DBA meet the requirements for the public interest task? The public interest mission must have a basis in law that is clear, precise and the application of which is predictable. The law ‘may’ contain additional provisions, but this is not necessary (see article 6(3) GDPR). in addition, it is required that all processing of personal data is necessary for the task of general interest. But how does this work in the case of a fairly loosely defined task that can be performed very differently per insolvency?

Round 2 / session 7

PLSC-STYLE PAPER DISCUSSION | ‘Comparing definitions of data and information in data protection law and machine learning: A useful way forward to meaningfully regulate algorithms?’

Raphaël Gellert

Abstract. The notion of information is central to data protection law, and to algorithms/machine learning. This centrality gives the impressions that algorithms are just yet another data processing operation to be regulated. A more careful analysis reveals a number of issues. The notion of personal data is notoriously under-defined, and attempts at clarification from an information theory perspective are also equivocal. The paper therefore attempts a clarification of the meaning of data and information in the context of information theory, which it uses in order to clarify the notion of personal data. In doing so, it shows that data protection law is grounded in the logic of knowledge communication, which stands in stark contrast with machine learning, which is predicated upon the logic of knowledge production, and hence, upon different definitions of data and information. This is what ultimately explains the failure of data protection to adequately regulate machine learning algorithms.